In Germany's fight against people smugglers, Chief Inspector Igor Weber's Pasewalk force is on the frontline.

Their patch includes part of the border area with Poland, a popular spot for people trying to cross illegally into Germany.

At the police headquarters, the chief inspector shows us a line of smugglers' vehicles, which were seized while trafficking illegal migrants.

One of them is a refrigerated van which has been stripped back to carry human cargo.

Inside, sodden sleeping bags and a few abandoned clothes are the only traces of the migrants who were moved like cattle for hundreds of miles.

Chief Inspector Weber says there were 18 people inside when they found the van.

There are no seats or seatbelts, just the hard, cold floor to sit on during the long journey.

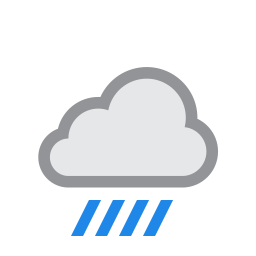

A hole in the roof left them exposed to the elements, so the rain could pour in, making conditions even more grim.

This isn't a one-off.

Officers show us pictures of other illegal migrants they have stopped.

One shows nine East Africans found crammed in a car, again without seats or seatbelts.

In another, 16 exhausted Somalis rest on the grass.

Many of the migrants have been travelling for months.

Route to Germany

After leaving Africa, the Middle East or Asia, Chief Inspector Weber says lots of people now come via Russia, travelling through Belarus, into Latvia, Lithuania and on to Poland.

They keep driving until they cross into northeastern Germany and straight into the patch patrolled by the Pasewalk force.

As a result, the fight against illegal migration has become a daily game of cat and mouse.

Germany's border with Poland is more than 400km (249 miles) long, surrounded by huge stretches of isolated farmland, dense forest and small villages. The perfect place to hide.

Throughout the day, the chief inspector takes us to different areas which have become crossing hotspots.

We drive to a quiet checkpoint surrounded by fields, which we are told is one of the places people traffickers try their luck.

It's manned by two Polish guards when we arrive.

The chief inspector explains the smugglers send a spotter car out to the top of a small hill above the checkpoint.

From there, the countryside opens up, allowing them to see if there are any controls in place. If there aren't, the smugglers then drive in with the illegal migrants.

The smugglers take a photo of them in front of a sign proving they have brought them to Germany and then leave the migrants to walk the rest of their journey alone.

It's a complex and well-funded criminal racket.

'Insidious' smuggling business

But the German government has had enough. Border checks have been tightened up and asylum rules made stricter.

We watch as police search the cross-border train, looking for anyone trying to sneak in that way.

But as we drive around rural routes filled with hiding places, the challenge facing authorities is clear.

"Is it possible for you to stop all illegal migrants?" I ask the chief inspector.

"No," he replies. "No border is 100% closed - that doesn't exist. In my professional experience, people always manage to overcome even the biggest walls or fences, but you can make that more difficult."

It seems Germany has done just that: in 2025, illegal entries were down 25% compared with the year before, according to figures from the interior ministry.

"Who do you think's winning? The police and border control, or the smugglers?" I ask.

"There are no winners in this business. The biggest losers are the migrants. That's just the way it is. Smuggling is a very insidious business - it's all about money," Chief Inspector Weber replies.

Hardening views

Germany's attitude to asylum seekers has radically changed.

In 2015, people cheered as refugees arrived at German train stations under Chancellor Angela Merkel's open-door policy.

The move saw more than a million, mainly Afghan and Syrian asylum seekers, enter in a year.

In the past decade, views have hardened.

The far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party has soared in the polls, fuelled by its anti-immigration policy.

In response, the ruling coalition has also got tough; by November 2025, deportations were already up 15% on 2024.

But some recent deportation flights have been controversial.

In the summer, a plane carried 81 criminals back to Afghanistan, while in December, Germany deported a convicted criminal to Syria for the first time since the start of a 14-year-long civil war.

Now the government is hoping to strike a deal to deport more Afghans as well as return Syrians.

Read more:

Inside smuggling trade bringing migrants from Africa

Man who supplied boats to people smugglers jailed

Despite criticism from human rights groups, it is standing by its policy.

"It is necessary we show the people that we are able to control who is coming to Germany and who [is] not," Germany's foreign minister Johann Wadephul told me at a recent news conference.

"So that is the deeper reason why we are controlling the borders now, and we are doing this in accordance with international law."

Traditionally the EU country which took the most asylum seekers, Germany has slashed first-time applications by more than half so far this year.

The government says it's proof its stricter policies are working.

But as Germany toughens up its asylum system, nearly a million people are living with rejections, and the largest number are from Afghanistan.

They say they're living in limbo.

'I'm not a criminal'

At a church in Berlin, I meet Sayed who has just found out his application has been rejected.

He says returning to Afghanistan is a death sentence.

Terrified, he asks us not to show his face as he tells me his story.

"They [the German authorities] rejected me and said it's safe to go back to Afghanistan," he explains.

"Everyone knows the consequences if a believer goes to Afghanistan. They won't survive there."

I ask him if there's any reason he can think of for the rejection?

"I have never done anything wrong in my whole life and I'm not a criminal," he replies.

For his pastor, Dr Gottfried Martens, it's a sadly familiar story.

His congregation includes 1,400 asylum seekers from Afghanistan and Iran.

He believes asylum applications have fallen not because of the government crackdown, but because of changes inside countries like Syria, where many refugees come from.

He says the tough new rules mean some of his congregation have already fled rather than risk being deported to Afghanistan.

"There has been a framing in the speeches of German politicians and for them, all Afghans are criminals," he says.

It's a claim ministers would refute.

Germany's problem may soon become UK's

I ask what those who have had their applications rejected will do now?

"Our people see no other way than to look for a country outside of the European Union, which is in fact the UK, because they know when they stay here then they will be dead pretty soon," he replies.

If the pastor is right, Germany's problem may soon become Britain's.

Those fleeing know since Brexit it's much harder for the UK to return people to Germany.

Whether Sayed joins a small boat crossing is undecided.

I ask if he understands the view of many Germans that they've taken some of the highest levels of asylum seekers in the world and enough is enough?

"Enough is enough? They are talking about human rights," he says. "As a human, it's my right to be free to live."

Looking at the statistics available for 2025, on paper Germany's crackdown seems to be working.

Initial figures show illegal migration is down, deportations are up and asylum applications have more than halved.

A new government in Syria and EU deals with other countries to curb the flow of migrants have undoubtedly also played a role.

But the question is, has Germany solved its migration problem or simply moved it on? Are those fleeing war and persecution now just paying smugglers to take them to other countries they hope are safe havens?

(c) Sky News 2026: There's a daily game of cat and mouse to catch illegal migrants in Germany - and

Iran's regime is more vulnerable than it has ever been, but Khamenei shows no sign of relenting

Iran's regime is more vulnerable than it has ever been, but Khamenei shows no sign of relenting

Russia strike leaves 1,000 Kyiv apartment blocks without heating

Russia strike leaves 1,000 Kyiv apartment blocks without heating

Human remains found as Australia continues to battle bushfires

Human remains found as Australia continues to battle bushfires

Nobel Institute responds to claims Maria Corina Machado could give Peace Prize to Donald Trump

Nobel Institute responds to claims Maria Corina Machado could give Peace Prize to Donald Trump

Bride and groom among eight killed in wedding gas cylinder blast

Bride and groom among eight killed in wedding gas cylinder blast

US military carries out large-scale strikes against Islamic State targets across Syria

US military carries out large-scale strikes against Islamic State targets across Syria

Former Newcastle goalkeeper Shay Given apologises after making Holocaust remark

Former Newcastle goalkeeper Shay Given apologises after making Holocaust remark

JD Vance agrees sexualised AI deepfakes 'entirely unacceptable,' Lammy says

JD Vance agrees sexualised AI deepfakes 'entirely unacceptable,' Lammy says